JOHN SMELCER

Insider/Outsider: Outcast Between Two Cultures

"What impresses me most about John Smelcer, aside from his powerful writing, is

his indomitable spirit. He has never given up; he has never let others quiet his voice.

He continues to write and the world continues to listen to what he has to say."

-James Welch, American Book Award winning author of Fools Crow & The Indian Lawyer

John Smelcer is a member of the Ahtna Native People of Alaska. The Ahtna People inhabit eight small villages, mostly located along the silty, glacial-fed Copper River, from which the word is derived ('Atna' tuu). Ahtna Native Corporation is one of the thirteen Native corporations established in 1971 by Congress under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), the largest indigenous land claims settlement in U.S. history. Under the Act, Ahtna was conveyed 1.6 million acres of land. Alaska Natives born before 1971 are tribal members (called shareholders) of one of the thirteen Native corporations. John Smelcer is a voting shareholder in Ahtna Native Corporation (Tazlina Village), a tribe recognized by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Only Alaska Natives are eligible to vote. John is the son of a half-blood Native father. John is a member of Tsisyu "Paint" Clan (pron. shish-you). Throughout most of the 1980s, John learned Traditional Native Ways of Knowing from his mentor, Walter Charley, who was related to his full-blood Indian grandmother, Mary Joe Smelcer. In the early 90's John built a little cabin on his BIA Native allotment land in Tazlina. For years, Dr. Smelcer was the tribally appointed executive director of the Ahtna Heritage Foundation. Over three decades, John's tribe has supported his undergraduate and graduate education with scholarships, including at Harvard University. In 1999, Ahtna Chief Harry Johns held a special ceremony to designate John Smelcer a Traditional Ahtna Culture Bearer, a term usually reserved for elders with significant cultural knowledge.

Click on "ethnicity" to learn more about John Smelcer's ethnicity, why he resigned from the University of Alaska, and about the willful ignorance of bullies who have relentlessly attacked him for decades despite the truth.

"John Smelcer is Alaska Native . . . just one voice among millions of Native Americans. His is a well-honed voice, however. There's much to be gained from listening to him." -Anchorage Daily News

"Smelcer's prose is lyrical, straightforward, and brilliant...authentic Native Alaskan storytelling at its best."

-School Library Journal

Dr. John Smelcer pursued a largely subsistence lifestyle, something of which his grandmother was very proud. John always shared his moose meat and caribou meat and salmon with his grandmother and her older sister, Morrie Secondchief, both born in Tazlina

Lake Village, which was abandoned long ago. They called John "Canaani," which in Ahtna means "Him with Hunter's Luck." He frequently brought porcupine to Morrie’s husband, Joe Secondchief, who was one of those very rare elders who never learned to speak much English. Over four decades, John Smelcer has participated in dozens of potlatches across

Alaska, including the potlatch for Ahtna Chief Harry Johns and Chief Walter Northway of Northway Village, who, it is said, was 117 years old when he died! John has been part of the hosting family on

numerous occasions, such as when his great aunt and great uncle, Morrie and Joe Secondchief, died, and when his beloved uncle and grandmother, Herbert

and Mary Smelcer, died. This practice of sharing resources is at the very heart and soul of

subsistence living in Alaska. As was once the case in Indian communities all across America for almost a century, many of John’s Indian relatives were sent away by the government to distant boarding

schools, where, among other hardships, they were prevented from speaking their own language. In the 1890s, the federal government outlawed the potlatch in Pacific Northwest Indian cultures. John's

great grandfather, Tazlina Joe, was instrumental in taking the potlatch underground until the government eventually lifted the ban sometime around the 1920s or 1930s. During those decades,

traditional ceremonies and dances across Indian Country were outlawed by the government.

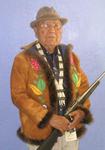

All his life, John Smelcer was raised to know traditional Indian ways. His father and uncle taught him especially how to hunt and fish and how to exist on the land—above all, to respect it. At his father’s encouragement, John attended Army training in mountaineering and arctic survival, sometimes at fifty or sixty degrees below zero, even though John was still in junior high and high school. They did everything those officer cadets did! As a young boy, John spent part of his summers living at Tazlina Village with his Uncle Herb who instructed John in Native Ways, as is tradition (see photo below). During the visit pictured, Uncle Herb bought John a Bowie knife at an Military Surplus store in Anchorage. Even back then, Uncle Herb encouraged local elders to pass on their knowledge to John. John sometimes spent part of the summers staying with his full-blood Native grandmother in Glennallen. As a schoolboy, John was involved in special programs for Alaska Native schoolchildren. In 1978, while in eighth grade, John was selected by the Fairbanks School District to participate in an exchange program sponsored by the Johnson O’Malley Program, a federally funded program for Alaska Native/Native American schoolchildren. Indian students from Fairbanks were sent to Nulato, a Native community on the Yukon River to participate in a week-long annual Native ceremony called the Stick Dance. John spent his junior year as a foreign exchange student in Sweden. During his senior year back home at Lathrop High School, and on recommendation of U. S. Senator Ted Stevens, John was awarded a four-year Army ROTC scholarship to attend any university in America. Senator Stevens had considered John for an appointment at West Point. Wanting to stay close to home, John choose the University of Alaska-Fairbanks. In the summer before beginning university, John got a job mapping the Arctic coastline. All summer long, John explored the region by foot and by kayak, encountering polar bears and walrus and discovering a frozen wholly mammoth that had been partially unearthed along a creek bed in Demarcation Bay near the Canadian border.

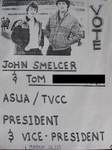

In the early-to-mid 1970s, John Smelcer was a Cub Scout and Boy Scout (see photo below). He earned one of Scouting's most prestigious medals. In 1979, John was in the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) in Fairbanks, Alaska studying to earn his pilot's license. In the mid-1990s, John was a Cub Scout Den Leader and later a Cub Master. Nowadays, John volunteers for Girl Scouts. His two daughters, almost a quarter century in age difference, were both Girl Scouts. His wife is a Girl Scout leader. Throughout the 1980s, John was a student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF), earning bachelor degrees in anthropology and archaeology, English, and education, and taking graduate courses in creative writing. John became friends with James Michener, the famous author who was doing research in the university's Rasmuson Library for a book he was writing on the history of Alaska. The book, ALASKA, came out in 1988. The two went to lunch together weekly in the cafeteria in the William Rasmusson Wood Center Student Union Building. They always ordered from the baked potato bar. Michener told famed mythologist, Joseph Campbell, about John's efforts in collecting Alaska Native myths (Campbell's interest in mythology began as a young man while studying the myths of American Indians). During the 1980s, John Smelcer was mentored by Ahtna elder and respected culture bearer Walter Charley, learning almost forgotten Ahtna Ways of Knowing. Walter was a respected Alaska Native leader, one of the first members of the Alaska Native Brotherhood. He served as comissioner of Wrangell -St. Elias National Park, the largest national park in America. He also served as vice president of the Aboriginal Senior Citizens of Alaska. For his lifetime of championing Native rights and issues, the Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) named him Citizen of the Year in 1988. Always a leader, John ran for UAF Student Association president in 1984 (see poster below). After graduating, John ran for the Board of Directors of UAF's Alumni Association. He lost to Joe Usibelli, Jr.

While a student at the UAF, John served in the United States Army Reserve, where he was trained in Arctic survival and warfare and mountaineering (see photos below). Several times he trained at the Army's Black Rapids Mountaineering School. Throughout the 1990s, John climbed all over Alaska. He eventually received an honorable discharge. In 2010, fellow alumni nominated John for UAF's Distinguished Alumni Award. In the summer of 1985, at the age of 22, John and his younger brother, James Ernest (family always called him Ernie), climbed 16,237 foot Mt. Sanford. Tragically, Ernie committed suicide in the spring of 1988, just weeks before his twenty-third birthday. Even in their early teens, John and Ernie hunted together in the perilous wilds of Alaska.

From 1978 to the mid-1990s, John Smelcer was a weightlifter and bodybuilder, setting numerous records, mostly in the 132 lb/60 kg class. Stories about him appeared in newspapers around the world (see photos below). At his last competition vying for the 1995 Mr. Top of the World title, John dropped weight to compete for the only time ever in the 123 lbs./56 kg. class and set his last record: an American record of 425 lbs. in the deadlift (see below; note the inner most plates on both sides of the bar weigh 100 lbs. each; the bar weighs 45 lbs. The photo was taken using Kodak Ektachrome slide film and no one seems to know how to convert it for me.) In his best shape, John could do thousands of sit-ups and slightly over a thousand push-ups. His gym teachers used to implore John to officially challenge the Guiness Book of World Records. (You should know the record for sit-ups is over 45,000 and the record for push-ups is over 10,000.) As a bodybuilder, John always used Van Halen's song "Jump" in his choreography. John even received a special presidential citation for his contribution to American sports from President Bill Clinton.

In 1992 and in 1993, John Smelcer was Director of Faculty for a unique, federally-funded program for rural Alaska Native/Native American high school seniors interested in careers in the allied health sciences. The program was housed at the University of Alaska Anchorage in partnership with the neighboring hospital where students interned. In 1993, Dr. Smelcer became a professor of English and Education at the University of Alaska Anchorage, where he co-chaired the Alaska Native Studies program and served as faculty adviser for the Alaska Native Students Club. In 1994, John was student-nominated for the Chancellor’s Award for Outstanding Service to Students. That same year, the president of the University of Alaska Statewide System personally appointed John to serve on a committee tasked with finding a new chancellor for the university. The summer after leaving the University of Alaska, Ahtna Native Corporation hired John as a tribal field archaeologist. John spent the summer living in a camper, tromping all over Ahtna’s lands in search of archaeological sites to identify and protect, and having frequent close encounters with moose and grizzly bears. He discovered and documented a number of abandoned villages and historical sites. The findings were published in The Archaeological Prehistory of the Kotsina, Copper and Chitina Rivers (1995). Around this time, John and his uncle Herb operated Copper River Indian Adventures, a Native-owned ecotourism river-rafting company.

In the winter of 1995, John was appointed by the Ahtna Board of Directors to serve as the executive director of Ahtna’s Heritage Foundation, a nonprofit organization

funded by the corporation to preserve the Ahtna language and culture, as well as to distribute over $150,000 in college scholarships annually to Ahtna shareholders and their descendants. John himself

had received scholarships from Ahtna throughout his college education. His uncle, Herbert Smelcer, was chairman of the Board of Directors. Herbert was an influential Alaska Native leader, serving

variously as president of Ahtna, Inc., as president of one of Ahtna’s subsidiary corporations, and as a member of the Board for decades. Herbert signed key legislation with President Carter. Hundreds

of important Alaska Native leaders attended Herb’s funeral service held at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage. John and his uncle spent a good deal of time together hunting, fishing,

snowmobiling, and operating the family’s subsistence fishwheel on the Copper River, just below its confluence with the Tazlina

River, which in Ahtna means “Swift River.” John's subsistence permit allowed him to catch 500 salmon a year. For

decades, Herb lovingly instructed his nephew in Native Ways of Knowing. Herb briefly served as the interim superintendant of

the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Alaska Interior Division. In that important post, Native villages often invited him to participate in cultural events. Several times, John was invited to accompany Herb

to participate in traditional hunts with Eskimo communities. When Herb graduated from Prince William Sound Community College in 1997 with an associate's degree in

business, John, then a adjunct professor at PWSCC, presented his uncle with his diploma.

From late 1995 until the summer of 1998, John Smelcer drove 170 miles each way to work at his tribal office in Glennallen,

living in his small, rustic cabin on his BIA Native land allotment without electricity or running water, television or telephone or a toilet, cutting firewood for a wood stove, and writing by the flickering yellow light of oil lamps. During his

tenure, he held over a hundred workshops with Ahtna elders to compile and publish a dictionary of the Ahtna language. The end result was that John became a living repository of the Ahtna

language with its four (now only three) distinct dialects. In the summer of 1998, John published a dictionary of nouns common to the language featuring a phonetic pronunciation guide. Today, aside

from a couple linguists, only John and a few elders speak the language fluently. He is the only tribal member who reads and writes in Ahtna fluently. During

1995-1998, John instituted an annual Culture Camp along the banks of the Copper River near Gulkana at which he and elders taught workshops on language, traditional storytelling, subsistence practices, clanship, potlatch dancing, and cultural history. He received a grant from the State of Alaska to create Positive Pathways, a language, culture, and literacy

program for Indian youth. John also worked with Ahtna elders to compile and publish a book of every existing myth in the memory of the culture. On the 25th

anniversary of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

(ANCSA), one of the boldest Indian legislation in U.S. history, John published An Act of Deception, a book that examined the negative impact of the Act on Alaska Native Peoples. John and former Alaska Federation of

Natives (AFN) president, Emil Notti, wrote introductions.

|

In 2003, John led a national protest against McDonald's for its erroneous policy of excluding Native Americans from their college scholarship program. Eventually, the NAACP (Julian Bond included), the Native American Rights Fund, and the Federation of Alaska Natives joined him, as well as a number of U.S. senators and congressmen (including decorated WWII veterans Sen. Daniel Inouye and Sen. Ted Stevens); a real David and Goliath story. John lost. McDonalds maintained its exclusionary policy in the belief that Native Americans are all rich from casino money and don't need their help, despite U.S. Census Bureau statistics to the contrary. That same year, John warned Timothy Treadwell (Grizzly Man) about the dangerous and unpredictable nature of bears, advice that Treadwell ignored at the cost of his and his girlfriend's lives. Twice, John served as a nominator for the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation's $625,000 MacArthur "Genius" Fellowships.

From the spring of 2004 until the summer of 2008, John was the tribally appointed director of Chenega Native Corporation’s Language and Cultural Preservation Project.

Chenega, the village corporation of the Native Village of Chenega Bay in Prince William Sound, is one of the most successful Native corporations in Alaska. As he did with his own tribe, John spent

several years working with elders to document and preserve the Alutiiq language and culture unique to the Chenega Bay region. During his tenure, he produced a series of innovative language posters,

two interactive language DVDs, and a noun dictionary of the Alutiiq language (click on dictionaries), making John one of only a handful of people able to speak, read, and write in that dialect of the

Alutiiq language. As well, he worked with elders to produce two important oral history books: We are the Land, We are the Sea and The Day That Cries Forever, a major contribution to Alaskan and Alaska Native history. In a book review in the Anchorage Daily

News, Alaska’s largest newspaper, The Day That Cries Forever was hailed as “must reading for every Alaskan.” The book was later adapted into

a play by the same name performed at The College of Wooster in Ohio. Around that same

time, Dr. Smelcer taught high school Classics and Alaska History at Alaska's premiere private academy in Anchorage. In 2007, Dr. Smelcer was director of Health

Education at the Alaska Native Medical Center/South Central Foundation. Around that same time, Dr. Smelcer taught high school Classics and Alaska History at Alaska's premiere private academy in Anchorage. In 2010,

John Smelcer was nominated by former students to receive the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Distinguished Alumni Award.

Continuing its decade's long support of John's higher education, in the fall of 2022, the board of directors of Ahtna Native Corporation awarded Dr. Smelcer a scholarship to earn a special certificate/diploma from Harvard University (see photo below). The scholarship included tuition, airfare, and lodging in Boston. To reiterate, only enrolled tribal members are eligible to receive scholarships.

For over a quarter century, John Smelcer was the associate publisher and poetry editor of Rosebud, one of the premiere journals of contemporary literature in the nation. The Boston Globe once called Rosebud "the best literary quarterly in America." Over the decades, John solicited, edited and published many of the world's preeminent writers and pop icons. Through an agreement with Universal Pictures, Rosebud appeared on the film set of Anastasia Steele's literary magazine office in Fifty Shades Darker and Fifty Shades Freed. Nowadays, John serves with distinction as Rosebud's Senior Editor Emeritus. |

(Above photos: Dr. Amber Johnson interviewing Helen Marie (formerly Sister Mary Pius) about her friendship with Thomas Merton in Lee's Summit, Missouri; Alaska Native Medical Center/SouthCentral Foundation, Anchorage, Alaska. John Smelcer, far left, in first cohort of Harvard's certificate in Inclusive Leadership program.)

John Smelcer is married to Dr. Amber Johnson (above), a university professor and chair of the department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminal Justice. Dr. Johnson was the protégé and widow of Professor Lewis R. Binford, member of the Academy of Science and one of the most influential archaeologists of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. Professor Johnson's research has been published in such prestigious journals as Science. She is a descendant of seven of the pilgrims who attended the first Thanksgiving at Plymouth Colony in 1621, including Myles Standish, Stephen Hopkins, John Alden, and his wife, Priscilla Mullins. (Photo: Dr. Johnson during oral history interview for the Grimes-Smelcer Thomas Merton Collection, July 2015. Photo by John Smelcer.)

John Smelcer was raised in Alaska to know and to participate in Native Ways, beliefs, customs, and subsistence practices. Many respected Native elders--almost all of whom are gone now--passed on their cultural knowledge to John because he was the only member of the younger generation who was interested in learning such things. They entrusted John to pass on what he learned to the next generation. John never really knew his non-Native side of the family. Nowadays, John is one of the last speakers of his Native language, one of the most severely endangered languages on earth. He has dedicated his life to preserving his Ahtna heritage, language, myths, oral history, traditional Indian knowledge, archaeological sites, and he has taught literature, creative writing, public speaking, journalism, and Native Studies at colleges and universities for more than thirty years. Dr. John Smelcer's novels, short stories, poems, essays, screenplays and articles--many anchored in Alaskan culture--have been published and translated worldwide. Like you, John Smelcer is the product of the people who raised him and loved him and instructed him, as well as of a place and a culture. He can be no other.

sitemap verification more Info

Copyright 2009-2017 - John Smelcer Official Web Site